In September, I’m going to a Georgette Heyer day, where academics and writers will talk about this most wonderful of Regency romance writers.

Heyer was my introduction to Regencies (at the tender age of 10), and I continue to love her, a devotion my husband shares (he writes Regencies too).

And one of the things I loved about her was her use of words I’d never seen or heard before. Take this speech from the boy in The Toll-Gate:

‘I ain’t whiddled nothing, only as how Mollie shakes hands for a carrot. You don’t want to brush, Mr Chirk! Honest, he’s a bang-up cove, else I wouldn’t ha’ dubbed the jigger. And we got some rum peck and booze, Mr Chirk!’

Totally unfamiliar terms, and yet Heyer’s genius was in using these words from thieves’ cant in a way which made their meaning clear in the circumstances (as long as you knew that Mollie was a horse and Mr Chirk was about to leave, aka ‘brush’). But where did Heyer get them from, and what was thieves’ cant, anyway?

Thieves’ cant is simply the language used, not only by thieves, but by the members of the lowest rung of British society during the 18th and 19th centuries. It goes back much farther than that, obviously, but that’s when it began to get noticed by more respectable folk, during the huge boom in lexicography (dictionary-making) in the 1700s.

Thieves’ cant has two main purposes: to allow those who speak it to have conversations which aren’t comprehensible to outsiders, and to act as an ‘in-group’ signal. That is, when humans speak the same way, they feel more comfortable together, and having your own special slang is a great way to build group identity.

The ‘not comprehensible to outsiders’ had a very practical purpose: it allowed teams of thieves to work together in public without their victims understanding their plans. If one member of the gang told the other to ‘Nim the wiper from the rum cull,’ they could be reasonably sure that the ‘rum cull’ (rich fool) wouldn’t realise they were going to steal (nim) his handkerchief (wiper, probably edged with expensive lace).

But in Heyer’s world, it’s not only thieves and Bow Street Runners who talk like this. It’s often rich young men. Why? Because it was a fad for rich Regency boys to go slumming, and in those dives where they played cards and dice and drank Blue Ruin (gin), they picked up some slang, and brought it back to act as another kind of ‘in-group’ signalling: in this case, the group of privileged young males.

That kind of speech didn’t get into books of the time, however. So where did Heyer learn it?

From one or more of these books: Collection of Canting Words from Nathan Bailey's 1737 The New Canting Dictionary and the 1811 Lexicon Balatronicum based on Francis Grose's Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, and the glossary from the Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux, published in 1819. There are also other options, which you can find discussed here.

Most likely, Heyer got her words from Francis Grose’s dictionary.

The good news is, you can too! And unlike Heyer, you don’t have to wade through the whole thing to find the words you need. Because Regency writer Stephen Hart has made the whole thing searchable for us on his website.

And here I must add a disclaimer: Stephen Hart is my husband (an archaeologist by training and early career, and a database engineer in his later career).

That combination of skills makes his website (www.pascalbonenfant.com) absolutely the place to go if you want to know what thieves or young rich men called a horse (a prancer), or a woman (rum doxy for a fine woman, or mort – gentry mort for a well bred woman. You don’t want to hear the insults, of which there were many).

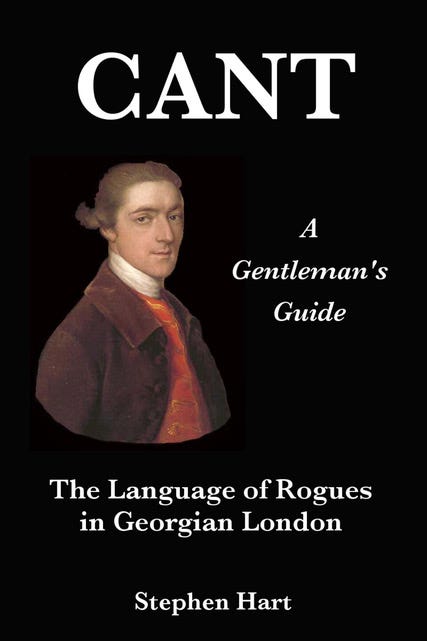

And if you can’t be bothered searching through the database, you can buy Stephen’s book, Cant, A Gentleman’s Guide, which is like a guide book to the slums of Georgian London (and is very funny, full not only of words but of true anecdotes from the period).

Here are a few insults you might find useful:

A piece of Sir Reverence (a turd)

Rantipole (a ‘rude romping boy or girl’)

Square toes ( an old man, because square-toed shoes were long out of fashion, and only worn by old men)

Holiday Bowler (a very bad bowler)

Ruffin (the devil).

I still love finding thieves’ cant in Regency romances, and thoroughly enjoy working out when I can use it in mine!

![The Toll-Gate: Gossip, scandal and an unforgettable Regency historical romance by [Georgette Heyer] The Toll-Gate: Gossip, scandal and an unforgettable Regency historical romance by [Georgette Heyer]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0rJK!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Feab2e238-bc5b-4c85-bc7e-cf64aad14873_325x500.jpeg)